THE HISTORICAL ENTERTAINING PSYCHOLOGY OF AMAZING FILM

HOW MOVING IMAGES REWIRED HUMAN MEMORY

PSYCHOLOGY OF AMAZING FILM – FILM AS A TECHNOLOGICAL DREAM

Film was not born as entertainment. It began as a mechanical experiment in capturing motion and preserving time. The earliest inventors were not storytellers but engineers and physicists. They wanted to understand how light, movement, and perception could be recorded. Film emerged from a convergence of photography, optics, and industrial machinery. It was a dream of freezing reality and replaying it at will.

This dream quickly became a cultural force. Moving images offered a new way to remember, imagine, and communicate. Film became a mirror, a mythmaker, and a memory machine. It reshaped how humans saw themselves and each other. From silent reels to digital cinema, film evolved into a psychological ecosystem. It carries emotion, ideology, and identity across generations.

Film Imagination

EARLY MOTION CAPTURE – THE BIRTH OF MECHANICAL MEMORY

Before film, motion was fleeting. The human eye could perceive movement, but it could not preserve it. In the 1870s, inventors began experimenting with devices that could simulate motion using sequential images. The zoetrope, phenakistoscope, and praxinoscope were early attempts to trick the eye into seeing movement. These devices used spinning discs and slotted cylinders to animate still drawings.

They laid the groundwork for cinematic illusion. In 1878, Eadweard Muybridge used multiple cameras to photograph a horse in motion. His experiment proved that sequential photography could capture real movement. This breakthrough was both scientific and symbolic. It showed that time could be dissected and reassembled. Motion capture became a form of mechanical memory. The camera became a witness, not just a tool. These early devices were not yet film, but they were its ancestors. They taught the world to see movement as a repeatable event. Film began as a study of motion, not emotion.

MOTION CAPTURE INVENTIONS AND THEIR FUNCTIONS

| Device Name | Year Invented | Function Description | Psychological Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zoetrope | 1834 | Spinning drum with slits and images | Illusion of movement |

| Phenakistoscope | 1832 | Rotating disc viewed in mirror | Visual rhythm |

| Praxinoscope | 1877 | Mirrors inside a spinning cylinder | Enhanced clarity |

| Muybridge’s Cameras | 1878 | Sequential photography of motion | Time dissection |

| Chronophotographic Gun | 1882 | Rifle-shaped camera for motion study | Motion as data |

PHOTOGRAPHY AS PRECURSOR TO FILM

Photography laid the foundation for film by proving that light could be captured and preserved. The first permanent photograph was created by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce in 1826. It required hours of exposure and produced a blurry image. Louis Daguerre improved the process in 1839 with the daguerreotype. These early photographs were static but revolutionary. They allowed people to see themselves and their world frozen in time. Photography introduced the idea of visual memory. It also introduced the concept of framing—choosing what to include and exclude. This framing would become central to film.

Photographs were emotional artifacts, not just technical achievements. They preserved weddings, wars, and wonders. As photography became more portable, it moved from studios to streets. The camera became a storyteller. Film inherited photography’s ability to document and dramatize. It added motion to memory. Photography was the still heartbeat that film would later animate.

PHOTOGRAPHIC MILESTONES AND THEIR LEGACY

| Innovation | Year | Description | Influence on Film |

|---|---|---|---|

| First permanent photo | 1826 | Niépce’s heliograph | Proof of light capture |

| Daguerreotype | 1839 | Silver-plated image process | Public fascination |

| Portable cameras | 1888 | Kodak’s roll film camera | Democratization of image |

| War photography | 1850s–1900s | Battlefield documentation | Emotional realism |

| Portraiture | 1840s onward | Studio-based identity capture | Character development |

THE INVENTION OF FILM STRIPS AND PROJECTORS

Film as we know it began with strips of celluloid. In the 1880s, inventors sought materials that could hold sequential images and run through machines. Celluloid was flexible, durable, and transparent. It became the backbone of early film reels. Thomas Edison and William Kennedy Laurie Dickson developed the Kinetoscope in 1891. It allowed one person to view moving images through a peephole. The Lumière brothers in France took it further. In 1895, they created the Cinématographe, which could record, develop, and project film. This made cinema a public experience. Film strips became communal memory.

The projector turned private viewing into shared emotion. Audiences gasped, laughed, and cried together. The screen became a social mirror. Film was no longer just a machine—it was a ritual. The projector was the priest, and the reel was the sermon.

EARLY FILM TECHNOLOGY AND ITS SOCIAL EFFECTS

| Invention | Year | Function | Cultural Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Celluloid film | 1889 | Flexible image carrier | Mass production |

| Kinetoscope | 1891 | Solo viewing device | Private entertainment |

| Cinématographe | 1895 | Camera and projector combo | Public cinema |

| Film reels | 1890s–1900s | Sequential image storage | Narrative continuity |

| Projection screens | 1895 onward | Enlarged communal viewing | Emotional synchronization |

SILENT CINEMA AS EMOTIONAL ARCHITECTURE

Silent cinema was not silent in feeling. It relied on exaggerated gestures, visual rhythm, and intertitles to convey emotion and story. Without spoken dialogue, actors used their bodies as expressive instruments. Directors framed scenes with symbolic lighting and spatial composition. Music played live in theaters, guiding emotional tone and pacing. Audiences learned to read faces, movements, and metaphors. Silent films taught viewers to feel through image rather than sound. This era produced iconic stars like Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton, whose performances blended comedy with pathos.

Silent cinema was not primitive—it was poetic. It explored themes of love, loss, injustice, and identity with visual precision. The absence of sound heightened emotional focus. Every glance, gesture, and cut carried symbolic weight. Silent films became emotional architecture, building feeling through form. They laid the foundation for cinematic language. Film began as a visual poem before it became a spoken story.

EMOTIONAL DEVICES IN SILENT CINEMA

| Technique | Function | Emotional Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Facial expression | Nonverbal communication | Empathy and clarity |

| Intertitles | Textual context | Narrative anchoring |

| Live music | Mood modulation | Emotional pacing |

| Lighting contrast | Symbolic tension | Visual drama |

| Physical comedy | Gesture exaggeration | Catharsis and release |

NARRATIVE STRUCTURE AS CINEMATIC BLUEPRINT

As film matured, it adopted narrative structure to organize emotion and meaning. Early films were short and episodic, often documenting real events or simple gags. By the 1910s, filmmakers began using three-act structure to shape stories. This structure included setup, conflict, and resolution. It mirrored classical storytelling traditions from theater and literature. Narrative structure gave film emotional rhythm and psychological depth. Characters became more complex, with goals, flaws, and transformations.

Plot became a vehicle for emotional journey. Editing techniques like cross-cutting and montage enhanced tension and perspective. Films like D. W. Griffith’s “The Birth of a Nation” and “Intolerance” demonstrated narrative ambition. Storytelling became cinematic architecture. The audience was guided through time, space, and emotion. Narrative structure allowed film to explore morality, identity, and consequence. It turned moving images into moral mirrors. Film became a blueprint for emotional experience.

ELEMENTS OF CINEMATIC NARRATIVE STRUCTURE

| Narrative Element | Function | Psychological Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Setup | Introduce characters/situation | Emotional grounding |

| Conflict | Create tension | Engagement and empathy |

| Resolution | Restore order | Emotional closure |

| Character arc | Show transformation | Identity rehearsal |

| Editing rhythm | Control pacing | Mood modulation |

SOUND INTEGRATION AS SENSORY EXPANSION

The arrival of synchronized sound in the late 1920s transformed film’s psychological reach. “The Jazz Singer” (1927) was the first feature-length film with synchronized dialogue. Sound added realism, intimacy, and emotional texture. Voices, music, and ambient noise deepened immersion. Dialogue allowed characters to express nuance and contradiction. Music became a tool for emotional manipulation and thematic reinforcement. Sound effects enhanced spatial awareness and tension.

The audience could now hear footsteps, whispers, and explosions. Sound expanded film’s sensory vocabulary. It also introduced new challenges in acting, directing, and editing. Silent stars struggled to adapt, while new performers emerged. Sound changed how stories were told and felt. It made film more immediate and visceral. The screen became a sonic landscape. Film evolved from visual rhythm to multisensory experience.

FUNCTIONS OF SOUND IN FILM

| Sound Element | Cinematic Role | Emotional Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Dialogue | Character expression | Intimacy and realism |

| Music score | Mood setting | Emotional amplification |

| Ambient sound | Environmental immersion | Spatial realism |

| Sound effects | Action enhancement | Tension and release |

| Silence | Contrast and emphasis | Psychological depth |

GENRE EVOLUTION AS SYMBOLIC CODING

Genres emerged as symbolic codes that shaped audience expectation and emotional response. Westerns, horror, romance, and comedy each carried distinct visual and narrative patterns. Genre allowed filmmakers to explore recurring themes with variation and depth. Westerns examined law, land, and masculinity. Horror explored fear, guilt, and the unknown. Romance dramatized desire, vulnerability, and connection. Comedy offered relief, critique, and catharsis. Genres became emotional contracts between filmmakers and viewers. They provided structure while allowing innovation.

Subgenres and hybrids expanded the emotional palette. Film noir blended crime with existential dread. Science fiction explored technology and identity. Genre evolution reflected cultural shifts and psychological needs. Audiences sought different genres during war, peace, crisis, and change. Genre is not formula—it is emotional architecture. It codes feeling through form. Film uses genre to rehearse collective emotion.

GENRE TYPES AND THEIR PSYCHOLOGICAL THEMES

| Genre | Core Theme | Emotional Function |

|---|---|---|

| Western | Frontier and justice | Moral clarity |

| Horror | Fear and survival | Catharsis and anxiety |

| Romance | Love and vulnerability | Emotional connection |

| Comedy | Absurdity and relief | Laughter and critique |

| Science fiction | Future and identity | Imagination and awe |

PSYCHOLOGICAL IMMERSION THROUGH CINEMATIC TECHNIQUE

Film immerses viewers by aligning sensory input with emotional rhythm. Techniques like close-up, tracking shot, and montage guide attention and feeling. The close-up reveals emotional detail and intimacy. The tracking shot creates movement and momentum. Montage compresses time and intensifies emotion. These techniques are not just visual—they are psychological. They shape how viewers feel, remember, and interpret. Immersion depends on pacing, framing, and sound design. The viewer becomes emotionally synchronized with the screen. This synchronization creates empathy, suspense, and identification. Film becomes a simulation of experience. It allows viewers to rehearse emotion safely. Immersion is not escape—it is engagement. The screen becomes a mirror of inner life. Cinematic technique is emotional choreography. Film directs feeling through form.

IMMERSIVE TECHNIQUES AND THEIR EMOTIONAL EFFECTS

| Technique | Cinematic Function | Psychological Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Close-up | Emotional focus | Intimacy and empathy |

| Tracking shot | Spatial movement | Engagement and flow |

| Montage | Time compression | Emotional intensity |

| Sound design | Mood shaping | Sensory immersion |

| Lighting contrast | Symbolic emphasis | Emotional clarity |

GLOBAL EXPANSION AS CINEMATIC LANGUAGE

Film did not remain a Western invention. It spread rapidly across continents, adapting to local cultures and storytelling traditions. In Japan, filmmakers like Yasujirō Ozu and Akira Kurosawa used film to explore family, honor, and silence. In India, Satyajit Ray and Bollywood studios created emotional epics rooted in music and myth. Soviet cinema developed montage theory, using editing to shape ideology and emotion. African filmmakers used film to reclaim narrative sovereignty and resist colonial distortion.

Latin American cinema blended realism with political critique. Each region developed its own cinematic grammar. Film became a global language with local dialects. It reflected cultural values, historical trauma, and symbolic rituals. Audiences saw themselves on screen—or saw what they were denied. Global cinema expanded empathy and perspective. It challenged monoculture and celebrated multiplicity. Film became a mirror with many faces. The screen became a site of cultural translation.

GLOBAL CINEMAS AND THEIR THEMES

| Region | Cinematic Focus | Emotional Signature |

|---|---|---|

| Japan | Family and silence | Restraint and depth |

| India | Music and myth | Spectacle and devotion |

| Soviet Union | Ideology and montage | Urgency and control |

| Africa | Resistance and ritual | Reclamation and pride |

| Latin America | Realism and critique | Passion and protest |

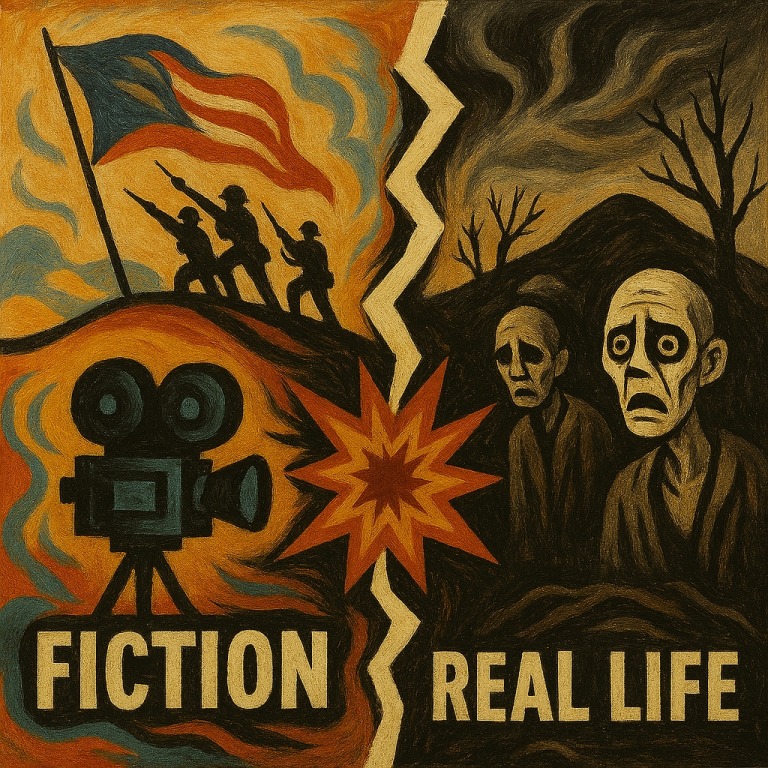

PROPAGANDA AS PSYCHOLOGICAL TOOL

Film has been used not only to entertain but to persuade. Governments quickly recognized its power to shape emotion and belief. In Nazi Germany, Leni Riefenstahl’s “Triumph of the Will” used cinematic spectacle to glorify authoritarianism. In the United States, WWII propaganda films promoted unity and sacrifice. Soviet cinema used montage to reinforce collectivist ideals. Propaganda films manipulate through rhythm, framing, and repetition. They bypass logic and appeal directly to emotion.

The screen becomes a battlefield for ideology. Viewers are not just entertained—they are conditioned. Propaganda uses film’s immersive power to rewrite reality. It simplifies complexity and amplifies fear or pride. The psychological impact is lasting and often subconscious. Reclaiming film from propaganda requires critical literacy. Not all cinema is neutral. The camera can be a weapon or a window. Film must be read as well as watched.

PROPAGANDA TECHNIQUES IN FILM

| Technique | Function | Psychological Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Montage | Emotional pacing | Ideological immersion |

| Hero framing | Moral elevation | Identification |

| Repetition | Message reinforcement | Belief conditioning |

| Music cues | Emotional manipulation | Mood control |

| Symbolic contrast | Us vs. them | Tribalism |

PSYCHOLOGICAL REALISM IN CHARACTER AND STORY

Film evolved to explore not just action but emotion. Psychological realism became a dominant mode in post-war cinema. Directors like Ingmar Bergman, Michelangelo Antonioni, and John Cassavetes focused on internal conflict. Characters were no longer heroic symbols—they were flawed, complex, and contradictory. Dialogue became introspective. Cinematography reflected mood and mental state. Stories slowed down to allow emotional texture. Psychological realism invites viewers to feel rather than judge. It mirrors therapy, confession, and reflection. The screen becomes a space for vulnerability. This realism challenges spectacle and embraces silence. It honors ambiguity and emotional truth. Characters are not solved—they are explored. Film becomes a mirror of the mind. It teaches emotional literacy through narrative immersion.

ELEMENTS OF PSYCHOLOGICAL REALISM

| Technique | Narrative Role | Emotional Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Introspective dialogue | Character depth | Empathy and reflection |

| Long takes | Emotional pacing | Immersion and tension |

| Minimalist score | Mood framing | Quiet intensity |

| Ambiguous endings | Narrative openness | Emotional complexity |

| Close framing | Psychological intimacy | Viewer identification |

DIGITAL TRANSFORMATION AND CINEMATIC ACCESS

The digital revolution reshaped every aspect of film. Cameras became smaller, cheaper, and more powerful. Editing moved from physical splicing to software interfaces. Distribution shifted from theaters to streaming platforms. Filmmaking became more accessible and decentralized. Independent voices gained visibility. Audiences could watch films on phones, laptops, and tablets.

The screen became portable and personal. Digital effects expanded visual possibility. Animation, CGI, and virtual production blurred boundaries between real and imagined. Film became a hybrid of photography, code, and design. The democratization of tools changed who could tell stories. Digital cinema also raised questions about attention, immersion, and authenticity. The medium evolved, but the emotional core remained. Film still seeks to move, mirror, and remember. Digital transformation is not just technical—it is symbolic. It redefined the relationship between viewer, maker, and machine.

DIGITAL INNOVATIONS IN FILM

| Innovation | Function | Cultural Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Digital cameras | Portable image capture | Accessibility |

| Nonlinear editing | Flexible storytelling | Creative freedom |

| Streaming platforms | Global distribution | Audience expansion |

| CGI and VFX | Visual enhancement | Spectacle and fantasy |

| Mobile viewing | Personal access | Fragmented attention |

FILM AS CULTURAL MEMORY

Film preserves not just stories but eras. It captures fashion, speech, architecture, and ideology. Watching old films is like time travel. They show how people lived, loved, and feared. Film becomes a cultural archive. It stores emotional tone, social norms, and historical trauma. Documentaries preserve truth. Fiction preserves feeling. Film allows cultures to remember themselves. It also allows future generations to interpret the past. Cultural memory is not static—it is cinematic. The screen becomes a vault of collective experience. Film teaches history through emotion. It makes memory visible and audible. The camera becomes a witness across time. Cultural memory lives in reels, pixels, and performances. Film is not just entertainment—it is evidence.

FILM AS MEMORY PRESERVATION

| Memory Type | Cinematic Expression | Emotional Function |

|---|---|---|

| Historical trauma | Documentary and drama | Empathy and awareness |

| Social change | Period films | Reflection and critique |

| Cultural rituals | Ethnographic cinema | Preservation and pride |

| Generational shifts | Family narratives | Continuity and contrast |

| Political eras | Satire and realism | Interpretation and debate |

FACTUAL TIMELINE – KEY MOMENTS IN FILM HISTORY

| Year | Event | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| 1826 | First permanent photograph by Niépce | Birth of visual memory |

| 1878 | Muybridge’s motion studies | Proof that motion could be captured |

| 1889 | Celluloid film introduced | Enabled sequential image storage |

| 1891 | Edison’s Kinetoscope | First solo film viewing device |

| 1895 | Lumière brothers’ Cinématographe debut | Birth of public cinema |

| 1927 | “The Jazz Singer” released | First synchronized sound film |

| 1939 | “Gone with the Wind” and Technicolor boom | Color film enters mainstream |

| 1945–60s | Rise of psychological realism and auteur theory | Film becomes personal and introspective |

| 1977 | “Star Wars” and digital effects revolution | Spectacle and CGI reshape cinema |

| 1995 | “Toy Story” released | First fully computer-animated feature |

| 2007 | Netflix begins streaming | Distribution shifts to digital platforms |

| 2010s | Mobile and social media integration | Film becomes portable and participatory |

| 2020s | Virtual production and AI-assisted editing | Hybridization of cinema and technology |

CENSORSHIP AS CONTROL OF EMOTION

Film has always been subject to censorship. Governments, religious institutions, and studios have restricted content to shape public morality and political stability. Censorship is not just about removing scenes—it is about controlling emotional access. What viewers are allowed to feel is often dictated by what they are allowed to see. In the early 20th century, the Hays Code in the United States banned depictions of sexuality, crime, and rebellion. In other countries, censorship targeted political dissent, religious critique, or cultural taboos. These restrictions shaped how stories were told and which emotions were permitted. Filmmakers responded with metaphor, subtext, and coded language.

Censorship created a tension between expression and repression. It taught audiences to read between the lines. The psychological impact includes emotional suppression and symbolic distortion. Censorship is not neutral—it is ideological. It affects how cultures process trauma, desire, and truth. Reclaiming cinematic freedom means confronting the systems that silence it. Film must be allowed to feel fully.

CENSORSHIP SYSTEMS AND THEIR EMOTIONAL CONSEQUENCES

| Censorship Type | Restricted Content | Emotional Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Moral codes | Sexuality and rebellion | Shame and suppression |

| Political bans | Dissent and critique | Fear and conformity |

| Religious filters | Blasphemy and ritual | Emotional erasure |

| Studio control | Market-safe storytelling | Sanitized emotion |

| Viewer rating systems | Age-based access | Fragmented experience |

AUDIENCE PSYCHOLOGY AND COLLECTIVE RESPONSE

Film is not just made—it is received. Audience psychology studies how viewers respond to cinematic stimuli. Reactions are shaped by culture, context, and personal history. A horror film may trigger fear in one viewer and laughter in another. Collective viewing amplifies emotion through social contagion. Laughter, gasps, and silence ripple through theaters. Audience response is both individual and communal. It reflects shared values, anxieties, and desires. Filmmakers anticipate these reactions and design accordingly. Jump scares, emotional beats, and plot twists are crafted to provoke.

Audience psychology also informs marketing, genre trends, and box office success. Viewers bring their own emotional architecture to the screen. Film becomes a mirror of collective mood. Understanding audience psychology helps decode cultural shifts. It reveals what societies are ready to feel—or afraid to face. The viewer is not passive—they are a co-creator of meaning.

AUDIENCE RESPONSE PATTERNS

| Stimulus | Viewer Reaction | Psychological Function |

|---|---|---|

| Jump scare | Startle and release | Catharsis |

| Emotional climax | Tears or silence | Empathy and bonding |

| Comic timing | Laughter | Relief and critique |

| Moral dilemma | Debate and reflection | Ethical rehearsal |

| Ambiguous ending | Confusion or awe | Cognitive engagement |

ARCHIVAL PRESERVATION AS CULTURAL RESPONSIBILITY

Film is fragile. Celluloid decays, digital files corrupt, and formats become obsolete. Archival preservation is essential to protect cinematic history. Institutions like the Library of Congress, the British Film Institute, and UNESCO work to restore and store films. Preservation involves cleaning, digitizing, and cataloging. It also requires ethical decisions about what to save and how to present it. Lost films represent lost memory. Restoration revives cultural identity and emotional legacy. Archiving is not just technical—it is symbolic.

It affirms that film matters. Preservation allows future generations to access past emotions, aesthetics, and ideologies. It also enables critical re-evaluation. Archival work is slow, meticulous, and often invisible. Yet it is foundational to cultural continuity. Film must be preserved not just as art, but as evidence. The archive is a vault of emotional truth.

ARCHIVAL METHODS AND THEIR PURPOSES

| Preservation Method | Technical Function | Cultural Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Film cleaning | Remove physical damage | Visual clarity |

| Digitization | Format conversion | Long-term access |

| Metadata cataloging | Information tagging | Searchability |

| Restoration editing | Frame-by-frame repair | Authenticity |

| Climate-controlled storage | Prevent decay | Longevity |

FILM EDUCATION AS EMOTIONAL LITERACY

Teaching film is not just about technique—it is about emotional literacy. Students learn how images shape feeling, how sound guides mood, and how editing controls rhythm. Film education includes history, theory, and practice. It explores genre, narrative, and cultural context. Students analyze how films reflect and influence society. They learn to decode symbolism, subtext, and ideology. Film becomes a tool for empathy and critical thinking. Education empowers new voices to tell their stories.

It also trains viewers to watch with awareness. Film literacy reduces manipulation and increases understanding. Schools, universities, and workshops offer diverse approaches. Education democratizes access to cinematic language. It turns passive viewers into active interpreters. Film education is emotional training. It teaches how to feel, question, and create. The classroom becomes a rehearsal space for emotional truth.

COMPONENTS OF FILM EDUCATION

| Educational Focus | Learning Outcome | Emotional Skill |

|---|---|---|

| Film history | Contextual understanding | Cultural empathy |

| Cinematic technique | Creative expression | Emotional precision |

| Genre analysis | Pattern recognition | Expectation management |

| Narrative theory | Story structure | Emotional pacing |

| Critical viewing | Media literacy | Emotional discernment |

THE FUTURE OF CINEMATIC EXPERIENCE

Film is evolving beyond the screen. Virtual reality, augmented reality, and interactive storytelling are reshaping cinematic experience. Viewers may soon walk through stories, interact with characters, and change outcomes. The boundary between film and game is blurring. AI-generated scripts and performances raise questions about authorship and emotion. The future of film is immersive, adaptive, and participatory. It will challenge traditional roles of director, actor, and viewer. Emotional engagement may become personalized. Algorithms could tailor pacing, tone, and resolution to individual psychology.

This raises ethical questions about manipulation and authenticity. Yet the core remains unchanged. Film seeks to move, mirror, and remember. The future will expand its tools but preserve its purpose. Cinematic experience will become more intimate and expansive. The screen may dissolve, but the story will remain. Film will continue to evolve as emotional architecture.

EMERGING TRENDS IN CINEMATIC EXPERIENCE

| Innovation | Viewer Interaction | Emotional Potential |

|---|---|---|

| Virtual reality | Immersive navigation | Embodied empathy |

| Interactive narratives | Choice-based storytelling | Agency and reflection |

| AI-generated content | Adaptive emotion | Personal resonance |

| Augmented reality | Real-world overlay | Contextual immersion |

| Biometric feedback | Emotion-responsive pacing | Mood synchronization |

CONCLUSION – FILM IS MEMORY IN MOTION

Film is not just a medium—it is a mirror, a map, and a mnemonic. It captures movement, emotion, and meaning across time. From mechanical experiments to digital immersion, film has evolved into a symbolic ecosystem. It teaches us how to feel, remember, and imagine. The screen is not passive—it is participatory. Every frame carries cultural weight and emotional resonance. Film is a ritual of recognition.

It allows us to rehearse identity, confront history, and explore possibility. The camera is not just a lens—it is a witness. Film is memory in motion, emotion in rhythm, and truth in metaphor. It is not just entertainment—it is evidence of how we see and who we are. The history of film is the history of human perception. And the future of film is the future of emotional literacy.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

What film first made you feel seen or understood How do you interpret the emotional architecture of cinema? Which cinematic moments shaped your memory or identity ?

FilmHistory #CinematicMemory #VisualCulture #EmotionalArchitecture #MovingImages #CinemaAsMirror #CulturalArchive #PsychologyOfFilm #NarrativeDesign #SymbolicStorytelling #GlobalCinema #DigitalFilm #EmotiveEditing #ScreenAsWitness #MemoryInMotion